The Consumer Trap: When Wrong Assumptions Costs Money!

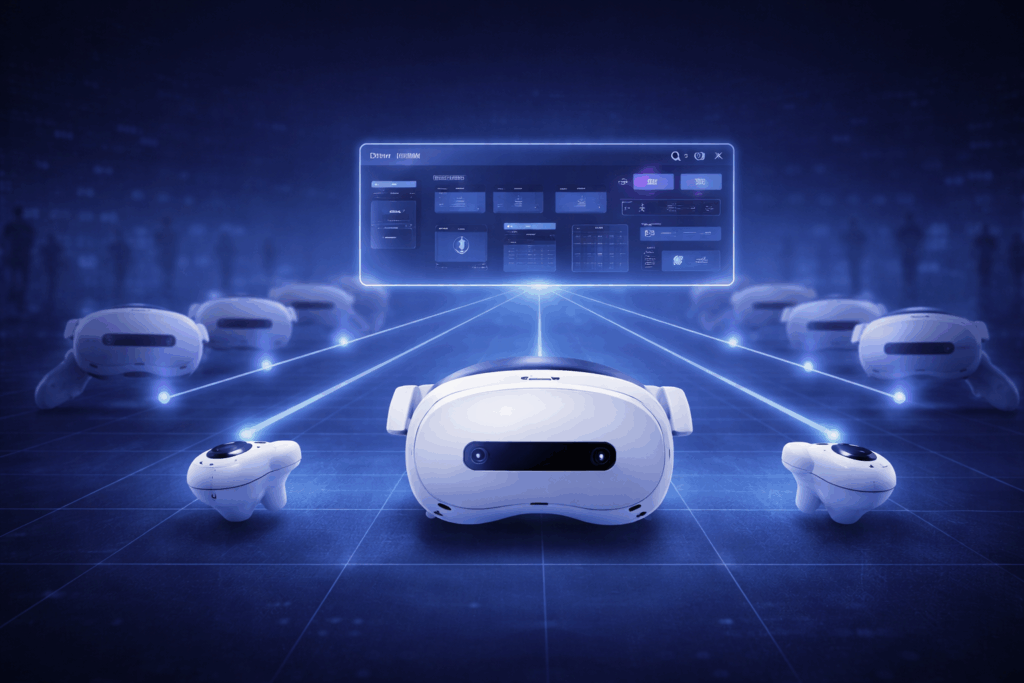

Free roam experiences are shaped by hardware, LBE VR compatible platform with device management, and whether the content is designed for commercial operation. In Week 1 we showed how free roam exposes system weaknesses that room-scale setups can hide. This article looks at a related issue: what happens when a venue is built on consumer assumptions about hardware (headsets), accounts, device behavior, and testing environments. The result is not noticeable immediately and doesn’t lead to catastrophic failure, rather it is about an accumulation of mismatches resulting in lost time, higher operating cost with higher number of employees, and avoidable operational risks as bookings grow. Why Consumer Thinking Enter into Commercial Venues When many operators first look at VR, the path seems obvious: buy a few Meta Quest headsets, use personal accounts to get started quickly, and install the same versions of games people play at home. It feels like a low‑risk way to “test” demand before investing in more professional infrastructure. But what works for a single or even multiple headsets in a quiet living room rarely works well on a busy Saturday, for a birthday group, and a free roam arena where six to eight players move simultaneously. In Week 1, we looked at how free roam exposes weaknesses that never appear in room‑scale testing. The same principle applies to consumer hardware and software assumptions. Problems that stay invisible in small demos, account issues, UI changes, and license constraints, suddenly become operational and financial risks once VR becomes a core attraction instead of an experiment. Assumption 1: Personal Accounts Are Fine if It Works A common pattern in new venues is to treat headsets a bit like phones: log in with whatever Meta account is available, install games, and let staff “just make it work.” In the short term, this feels fast and flexible. Over time, it creates a fragile foundation for a commercial operation. Meta’s own supplemental terms specify that commercial or business use of their products is subject to separate commercial terms, and that organizations must agree to those terms when using devices beyond personal purposes. When staff rely on personal or ad‑hoc accounts, several risks emerge at once. Accounts can be locked, disabled, or changed without reference to the venue’s needs if policies change or credentials are lost. Content libraries may technically belong to individuals rather than the business, complicating control when staff leave or roles change and when access must be managed consistently across multiple devices. Consumer headsets also require preparatory steps such as enabling developer mode, managing organization accounts, and maintaining login state across devices. These steps are minor during setup but become recurring maintenance tasks over time, especially when devices reset, update, or change ownership. Assumption 2: Testing Commercial VR In A Consumer Environment Another common trap appears during evaluation. Many operators correctly reach out to licensing platforms such as SynthesisVR to test commercial titles, but the testing setup itself still mirrors a consumer environment. A single headset, manual calibration, and staff-guided interaction can appear stable during short demos. At low volume the system works. Once multiple players run simultaneously throughout the day, differences emerge. Free roam depends on repeatable behavior across every headset. When preparation steps rely on consumer workflows, staff must handle per-device setup, alignment, and interface interaction between sessions. The content may be licensed correctly, but the operating conditions have not yet been tested. Because of this, a setup that feels reliable during evaluation can require constant intervention during real operation. The issue is not the game version alone, but whether the environment used for testing reflects continuous public use. Assumption 3: Updates and UI Changes Are Inconvenient, Not Catastrophic Consumer devices are designed to evolve quickly. Firmware updates, interface redesigns, and new features are part of the normal lifecycle for home users. In a living room, a changed menu or unexpected update is a minor annoyance. In a venue with back-to-back bookings, it can disrupt an entire peak period. Operators sometimes expect that standalone device management tools or business account configurations will stabilize the experience. These tools help deploy applications and manage devices remotely, but they do not change how the headset behaves during a live session. Interaction flows, recenter actions, boundary prompts, and other user-level controls still follow consumer logic. In small room-scale demos this difference is easy to overlook. In free roam and high-throughput environments it becomes operational friction. Staff must guide players through menus, correct unintended inputs, or re-establish alignment between sessions. A system can function correctly and still interrupt venue flow. The problem is not a single update. It is that the operational behavior of the device remains designed for an individual user rather than a continuous public attraction. Legal, Warranty, and Liability Risks of Consumer‑First Devices Beyond day‑to‑day operations, there is a structural issue: consumer hardware and content are not written with arcades and free roam arenas as the default use case. Meta’s supplemental terms specify that commercial or business use is subject to additional commercial terms for each product, and that any organization using devices for non‑personal purposes must have the authority to bind itself to those terms. This is a clear signal that consumer purchase alone does not automatically grant the right to run public, paid experiences. When consumer terms are used in public paid environments, support expectations and liability boundaries become less clear. For a business built around scheduled sessions, unclear responsibility introduces unnecessary operational risk. These operational differences are often underestimated because the initial hardware price is visible immediately, while the operational impact appears gradually. Why “Saving a Few Hundred Dollars” Increases Your Operating Costs Operational cost differences often appear as staff time rather than hardware price. In large-area experiences, manual calibration, drift correction, and interface handling accumulate across the day. Industry comparisons show consumer-oriented setups can require roughly three times more daily staff interaction per headset, about 60 minutes versus 20 minutes on LBE-focused systems. The hardware price difference is visible on day one, but the labor difference